Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Paata Gugushvili Institute of Economics International Scientific

CHALLENGES OF PROVIDING PENSION COVERAGE TO ALL: PUBLIC EXPOSURE TO DEMOGRAPHIC FISCAL RISKS IN GEORGIA

Abstract.The article reviews analytical literature on the demographic challenges worldwide. It is aimed at contributing to the debate over the increasing necessity to improve social security of elderly workers both in developed and developing countries. The ways to make government-led pension systems sustainable should be discussed further. The challenges related to the fiscal risks associated with the public pension system in Georgia are also discussed.

Key words: population aging, demographic challenges, pensions, social protection, fiscal risks

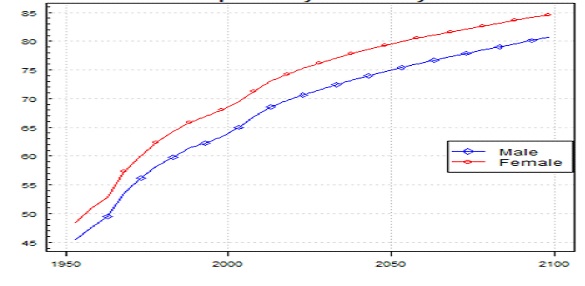

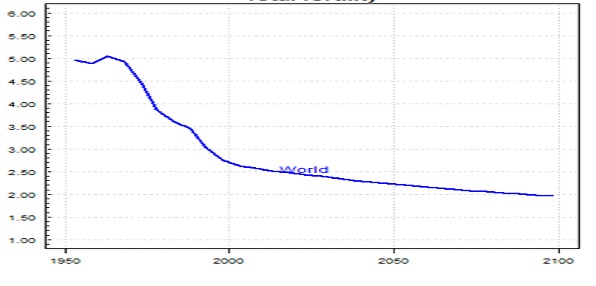

Population ageing as a global demographic trend has already influenced social processes, patterns and structures such as labor, family, work and employment, etc. The relevant literature concludes that population ageing is due to increasing longevity; low and below-replacement rate fertility and, also emigration trends that significantly impacts in particular smaller countries, for instance in Eastern Europe (OECD, 2013). Nowadays most countries are seeing significant population aging; Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the trends in life expectancy and fertility rates.

Figure 1. Life expectancy at birth by sex, 1950 – 2100.

Data source: United Nations

Figure 2. Total fertility, 1950 – 2100.

Data source: United Nations

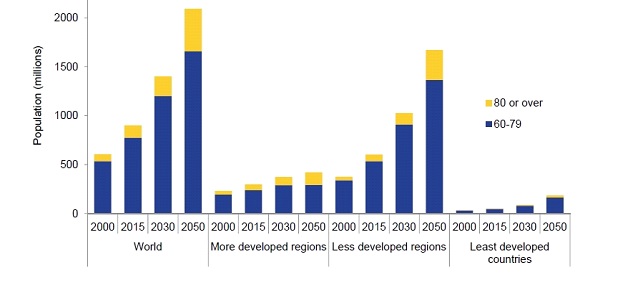

Population aging trends look rather critical in the context of most effected regions and countries. According to the recent reports published by the United Nations the global population aged 60 years or over numbered 962 million in 2017 is expected to double by 2050, when it is projected to reach nearly 2.1 billion (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Population aged 60-79 years and aged 80 years or over

by development group, 2000-2050

Data source: United Nations

What is also very important, the number of oldest-old (persons aged 80 years or over) around the world is growing at the fastest rate and is projected to increase more than threefold between 2017 and 2050, rising from 137 million to 425 million. In 2050, older persons (60+) are expected to account for 35 percent of the population in Europe, 28 percent in Northern America, 25 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 24 percent in Asia, 23 percent in Oceania and 9 per cent in Africa (UN, 2017 and UN, 2022).

At the same time life expectancy at age 60 is increasing in all country groups and regions and the old-age dependency ratios will almost double by 2050 in a vast number of developed and emerging countries. If there is a higher life expectancy in the future it would definitely mean that life for most populations throughout the world will become more expensive because of increase in health and care costs at older ages. This means that ageing trend worldwide may come along with more severe and persistent poverty, as many can easily fall into poverty after they stop working.

The International Actuarial Association (2016) highlights that worldwide longevity, and particularly healthier longer lives, are greater for people in higher socioeconomic groups. This evidence suggests that poor and vulnerable elderly in developing, emerging, and developed countries will demand more financial support than today (WB, 2011; UN, 2010).

While there is a clear need to improve the position of both current and future vulnerable old-age populations through social protection contributory and non-contributory tax financed schemes, fiscal consolidation or austerity pressures in most developed, emerging and developing countries continue to jeopardize the long-term adequacy of pensions (ILO, 2017).

The ILO Social Protection Report (2017) highlights that the vast number of countries including the most developed are proposing parametric and systemic reforms aiming to achieve fiscal sustainability of their pension systems, though they lack the potential to maintain pension adequacy in the future, and if nothing is done the future beneficiaries will be less better off or simply will get poor. The report highlights that in most developed countries with comprehensive and mature systems of social protection, the main challenge with ageing populations is to maintain a good balance between financial sustainability and pension adequacy.

A number of research studies suggest that in most OECD countries future retirees will face greater financial risks. Most people are already not saving enough, and ageing makes managing their finances harder for them. For instance, in the US, while the majority of current retirees can weather shocks such as high medical bills, future retirees would be much more vulnerable to such shocks (CRR, 2018).

Not surprisingly, the situation is harder in less developed economies that are facing structural barriers linked to development, insufficient fiscal space, high levels of informality, poverty, low contributory capacity, and are still struggling to develop and finance their pension systems. It is worth to mentioning that the trend related to the decline in intergenerational system of family support is becoming more and more obvious even in younger developing and emerging economies.

Most governments don’t directly influence demographics. But they implement changes to welfare programs, social insurance programs, social security programs, disability insurance programs, healthcare programs, long-term and end-of-life care programs, labor and employment programs, and what is of crucial importance, they undertake measures to improve access to financial inclusion. Consequently, the main challenge for both developed and developing world is to make policy efforts to implement either effective public or private services to provide financial security in old ages for the most vulnerable workers.

Research is needed around the Eastern European and Central Asian, i.e., including post-Soviet states, to assess the effects of population aging on social protections and fiscal risks amid a context of heightened regional and global economic uncertainty and to identify ways to adapt policies to those changes. Transition economies with traditional payroll-based pension systems and sizable informal and non-standard employment need special attention.

Fiscal policy response to the causes, consequences, and social policy implications of an increase in population aging trends, migration, informal and non-standard employment in Georgia should be analyzed amid a context of heightened public exposure to fiscal risks in the Caucasus.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) report “Fiscal Resilience and Social Protection Support Program” (2022) summarizes that while Georgia has significantly expanded its social protection provision, particularly since 2010, challenges remained. Among the most obvious challenges are those related to poverty and employment issues. High rates of poverty represented a significant challenge for Georgia in the years after independence in 1991. The country’s development has been hampered by periods of political instability and conflict. Furthermore, economic growth occurred mostly in urban areas, and particularly in the capital and nearly half of Georgia’s population lives in rural areas, and with limited education and training (49% of the workforce remains in sectors with low productivity such as subsistence agriculture, including substantial informal work).

Multiple analytical reports suggest that basic pension - universal old age pension has had a strong impact on reducing poverty rates since its inception and is likely to remain a powerful mechanism for old age poverty prevention. However, while playing an important role in poverty reduction, the old age social pension is not sufficient to be adequate to cover the expenditures of retirees.

According to the Georgian Statistical Agency social protection data (GeoStat, 2022) and the ADB analytical reports (ADB, 2021; 2022) there were about 800,000 receivers of the universal basic pension in 2022. Within the context of the demographic trends and the share of old age population growing, the number of recipients has been steadily increased over the years. Such a trend, along with high rates of informal labor, will put the government under the strain if it does not undergo major changes in the financing mechanism scheme to make it more viable and sustainable. The ADB reports (ADB, 2021; 2022) suggest that shrinking contribution revenues and swelling pension expenditures require that the government explores alternative measures for old age income provision, or the lives of retirees will be jeopardized, and those that are vulnerable and, hence, more prone to income shocks, will fall into extreme poverty. Multiple studies suggest that universal basic pension significantly reduces poverty rates among the elderly. Furthermore, it is obvious that the pension redistributive effect is substantial in multigenerational families and reduces child poverty significantly in Georgia.

The tax-financed basic pension - old-age pension program is the largest component of social protection expenditure, with 65% of the cumulative budgetary expenses for social welfare. Changing demographics pose significant threats to long-term fiscal sustainability in Georgia. Studies suggest that Georgia’s old-age dependency ratio is expected to increase from 25.9 in 2015 (one older adult supported by four working-age adults) to 55.9 (one older adult supported by just two working-age adults). At the same time, the share of the population eligible for universal pensions under the current policy arrangements with women retiring at age 60 and men at 65 is set to increase from 21.2% in 2021 to 27.6% in 2040.

Despite the fact that the universal pension plays a significant poverty reduction role, maintaining the adequacy of the social pension system would increase the primary budget deficit by between 1.9% and 3.3% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2069. As a result, government debt could increase up to between 88% to 122% of GDP in the same period on account of increased pension benefits. With the demographic composition steadily changing and the share of old-age population growing, financing old-age pensions solely through the government general revenues would be fiscally unsustainable. Exclusive reliance on the universal pension scheme would result in a doubling of pension expenditure by 2060, to about 10% of GDP and would amount to about a third of budget expenditure (ADB, 2022).

Increased public exposure to fiscal risks forced the government to implement measures in order to reform the pension system in Georgia. Policy options including adopting an indexation of the tax-financed basic social pension and the implementation of the pillar II mandatory contributory pension scheme was launched within the period of 2016-2018 (in combination with the existing universal old-age pension system) can provide significant support for the elderly and can potentially mitigate public exposure to high fiscal risks (Government of Georgia, 2016).

Currently, the Georgian retirement income landscape includes income from the basic noncontributory old-age pension, state compensation (pensions for civil service), the pillar II mandatory contributory pension scheme, private, voluntary defined-contribution pension schemes, and other forms of retirement income support, such as formal health care, traditional family support, home and land ownership, etc. However, the old-age pension is the largest system of public support for the elderly and is fundamental in terms of its coverage, spending, and its contribution to elderly consumption.

The basic pension, in terms of coverage, spending, and poverty reduction, is the pillar of the Georgian pension system and the largest source of public support for the elderly. It provides universal coverage for the elderly and is virtually complete. The old-age pension is a pay-as-you-go, universal, flat-rate pension financed by general budget revenues. Currently, the old-age pension is provided to all those reaching retirement age (age 65 for men and 60 for women). The pillar II mandatory contributory pension scheme is a promising one. The other components of the Georgian pension system, such as state compensation and existing voluntary pensions, have low coverage. State compensation was first introduced in 2006. It may be classified as a specific type of non-contributory public pension for civil service. State compensation is provided due to the importance of the work and services that specific workers perform for the state and civil society. State compensation aims to secure constitutional social protection for state and civil workers. State compensation provides a relatively generous retirement income.

Additionally, the voluntary pensions in Georgia are not yet developed. The Georgian voluntary private pension schemes – the third pillar – were implemented in 2007. These pension schemes in Georgia were founded by insurance companies. They were voluntary defined-contribution schemes offered by employers. The Georgian voluntary pension schemes provide unfettered access to pension savings, which are withdrawn for any purpose by their participants. The new law on “Voluntary Private Pensions” has been enacted in May 2023 and would provide more opportunities and incentives for workers to save.

Other forms of retirement income support include traditional ones. The most common source of retirement income support comes in the form of the generous access to informal traditional family support, as Georgians have a very strong sense of family and elderly care obligations. Among other sources of retirement income support are formal health care, access to individual financial assets (earnings from leasing, dividends, etc.), financial support from family members (such as remittances and gifts), and non-financial assets such as homeownership and land (Nutsubidze at al., 2017).

In order to address institutional fragilities in fiscal management and social protection in Georgia strengthening the adequacy and fiscal sustainability of social protection programs to protect the livelihoods of Georgia's aging population is of crucial importance.

The current fundamental pension policy framework that encompasses the combination of the public basic old-age social pension and the pillar II mandatory contributory pension scheme can potentially replace about 30-40 percent of working life average income for those working about forty years in their productive lives. However, not surprisingly, such a privilege is not available for those involved in informal and non-standard work, including self-employed (Nutsubidze, 2019). The statistical data available through the Georgian Pension Agency and the assumptions made, suggest that informal and non-standard workers particularly including women who currently represent about 70 percent of all retirees are the most vulnerable.

The pension reform process of the Georgian pension system should be enhanced by the measures undertaken in order to promote:

- Regular contribution payments among pension participants that include stimulating women and informal and non-standard workers, self-employed to contribute, as well as;

- The development of the III-pillar voluntary pension schemes and incentivize additional savings. Incentivizing voluntary savings, including occupational and individual savings based on defined contribution principles, stimulating participation in the labor force and enhancing participation and contribution enforcement mechanisms are becoming priority policy objectives;

- Implementing and enhancing a life-cycle approach to social protection system is a key to the betterment of the society in Georgia. The life-cycle social protection system should provide workers with adequate work-life and retirement earnings. A particular emphasis should be made on providing universal social protection for children. Additionally, skills development and job creation programs should be supported to contribute to the human capital and workforce development.

References

- ADB 2022. “Fiscal Resilience and Social Protection Support Program.” Report documents. Available at: www.adb.org

- ADB 2021. Report and Recommendation of the President. “Fiscal Resilience and Social Protection Support Program.” Available at: www.adb.org

- Geostat 2022. Social Protection indicators. National Statistical Office of Georgia. Available at: Social Protection - National Statistics Office of Georgia (geostat.ge)

- Government of Georgia 2016. “Report on the Pension System Reform,” prepared by the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development and the Ministry of Finance of Georgia.

- IAA 2016. Pensions, Benefits, and Social Security. Available at: Home (actuaries.org)

- CRR 2018. “Will the Financial Fragility of Retirees Increase?” By Steven A. Sass. Available at: Will the Financial Fragility of Retirees Increase? | Center for Retirement Research (bc.edu)

- ILO 2017. World Social Protection Report. Universal Social Protection to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals 2017-2019.” Geneva.

- Nutsubidze 2017. “The Challenge of Pension Reform in Georgia: Non-contributory Pensions and Elderly Poverty.” International Social Security Review. Volume 70, Issue 1, pages 79-108.

- Nutsubidze 2019. “Informal and Non-standard Employment: A Look at the Impact on Social Protection Policy ,” online issue. Available at: https://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/informal-and-non-standard-employment-a-look-at-the-impact-on-social-protection-policy/

- OECD 2013. Coping with emigration in Baltic and East European countries. Available at: Coping with Emigration in Baltic and East European Countries | OECD iLibrary (oecd-ilibrary.org)

- OECD 2018. “Pensions at a Glance. Asia and Pacific.” Publishing OECD, Paris, France. Available at: www.oecd.org

- UN 2017. “World Population Aging Report”. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf

- UN 2010. “World Population Ageing”, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Available at: World Population Ageing 2009 | Latest Major Publications - United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- UN 2022. World Population Prospects 2022. Available at: World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations

- WB 2009. “Is Latin America: Ready for an Aging Revolution?” Available at: Latin America: Ready for an Aging Revolution? (worldbank.org).